Research Projects

Levels of Legibility:

Roles and the Flow of State Information in French Morocco

2025, Social Science History, https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2025.10092

How do state actors interpret and share information? Theories of the state have long recognized the role of legibility – the modes and practices by which states render society and nature knowable through intervention and information collection – in constructing and maintaining state power. Yet, research has only begun to explore the processes by which information is created and diffused within state administrations. Drawing upon theories of agency relations in states, this article explores how administrators’ communicative practices shape knowledge and legibility. Through examining memos, legislative studies, and draft legislation for decrees recognizing water rights in the French Protectorate in Morocco, I identify a set of common patterns in the construction of bureaucratic information as it moves from street-level administrators to central officials. In analyzing these patterns, I demonstrate how administrators’ obligations and their understandings of the state’s political projects determined not only how French officials collected information, but what they communicated to others. As information moved across administrative levels, officials iteratively changed information. Joining critiques and extensions of legibility theory that emphasize the role of non-state actors in the construction of state knowledge, I argue that we must also attend to intra-state dynamics. In tracing communication and information, I demonstrate that information is iteratively constructed by state agents according to their administrative position and transformed by its particular bureaucratic routes. Modeling legibility and the development of state knowledge requires attending to administrators’ agency, their relationships with each other, and their understanding of the state’s goals.

Recurrent Continuity and the Reproduction of Colonial Policy in Independent Morocco

Under Review

Following independence from France in 1956, the Moroccan state enacted several land reforms to return agricultural lands to Moroccan ownership. While many postcolonial states have enacted land reforms, the Moroccan efforts are striking in their close mirroring—both in substance and order—of earlier French attempts to implant a settler population. Building from archival research in France and Morocco, the paper asks: why did the independent Moroccan state implement the same sequence of policies as its colonial predecessor? The approaches of historical persistence and path dependence have characterized the study of colonial legacies, yet neither can adequately conceptualize recurrent sequences or processes. The goals of this paper are twofold. First, I construct an approach to studying repeated sequences, recurrent continuity, to characterize cases in which an outcome, or sequences of outcomes, emerges independently from functionally equivalent conditions before and after a juncture. Second, I use this approach to explain the recurrence of Moroccan land reforms. I argue that both the colonial and independent states needed to secure control over the agricultural economy with low state capacity, requiring dependence on a patronage network. As states’ capacities increased with patronage support, elites expanded their demands, creating similar expanding trajectories of land reform.

Should I Stay or Should I Go? The Politics and Patterns of Settler Withdrawal in Independent Morocco

Working Paper

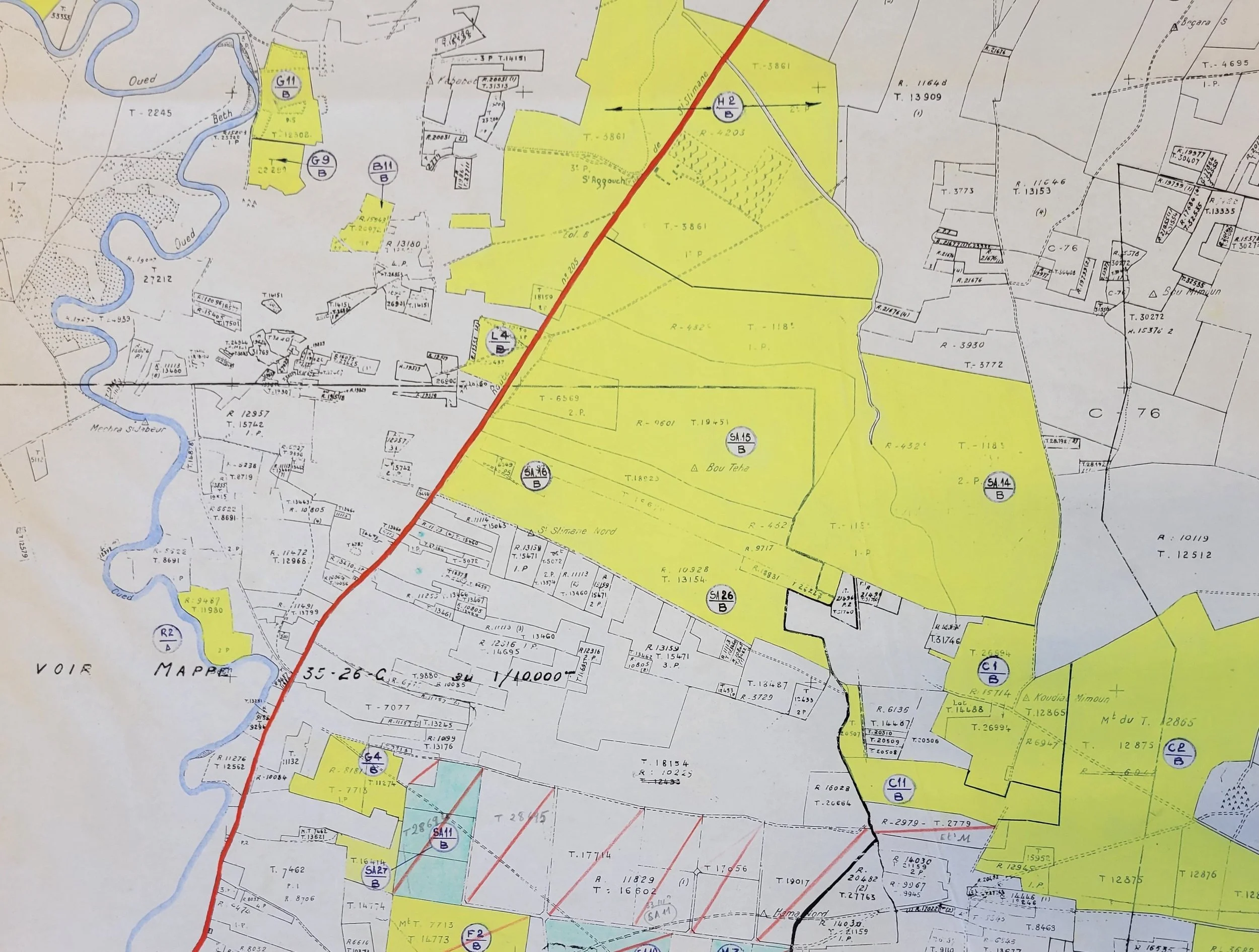

Why do settlers leave former colonies? Postcolonial regime change creates many disruptions that may prompt settlers to depart former colonies, ranging from the threat of violence, lack of political representation, political conflict, and withdrawal of economic support from a metropole. Yet, there are also reasons why settlers would be highly incentivized to remain in former colonies, including tightly-knit settler communities, the lower costs of living in former colonies, and the costs and risks of relocation to the metropole or elsewhere. Yet most significantly, many settlers own immovable assets in former colonies that they are reticent to abandon, such as agricultural land, heavy equipment, and manufacturing infrastructure. In this paper, I seek to understand what prompts settlers to divest, either by selling or abandoning their assets, and leave the former colony. To answer this question, I examine settler departures from Morocco following independence from France in 1956, where approximately one million hectares of agricultural land remained in European hands. Drawing from numerous archival sources, I construct an original longitudinal and geospatial dataset of settler land-holding at the property level from the end of the French Protectorate in Morocco in 1956 to the final expropriation of settler lands in 1973. Through longitudinal regression analysis of land sales, I find that settlers were differentially sensitive to changes in pressure from the Moroccan state and perceived risk of expropriation. At low levels of pressure, owners of both high and low-value properties were equally likely to divest and depart. As pressure and risk rose to moderate levels, those with fewer marginal benefits from continued investment (owners of low-value properties) became more likely to divest than those with higher potential returns (owners of high-value properties). At high levels of pressure and risk, that relation inverted: the owners of high-value properties, with higher potential losses from expropriation, became more likely to divest than owners of low-value properties. This variation in settler departure and the return of economic holdings to Moroccan ownership has significant theoretical and methodological implications for the study of colonial legacies.

Structured Spirituality: The Cross-Institutional Dynamics of ‘JewBus’

Forthcoming, Nova Religio

New Religious Movements, syncretic practices, and the spiritual-but-not-religious have challenged sociologists of religion to reexamine the structure of religious communities. Researchers have characterized these movements through two broad approaches, what I term the structural and movement-oriented approaches. The first explains phenomena through macrosocial models, while the latter describes the trajectory of individual movements in isolation from broader phenomena. Each approach includes rich explanations, but both obscure important religious features. I argue that religious movements must be conceptualized through what I term a ‘semi-autonomous’ approach that emphasizes the relationships between broad social changes and their enactment or rejection within communities. I demonstrate the necessity of this approach through an examination of JewBus—individuals who identify with both Judaism and Buddhism—and argue that one must analyze contemporary religious movements as both embedded within and partially autonomous from broader religious changes.